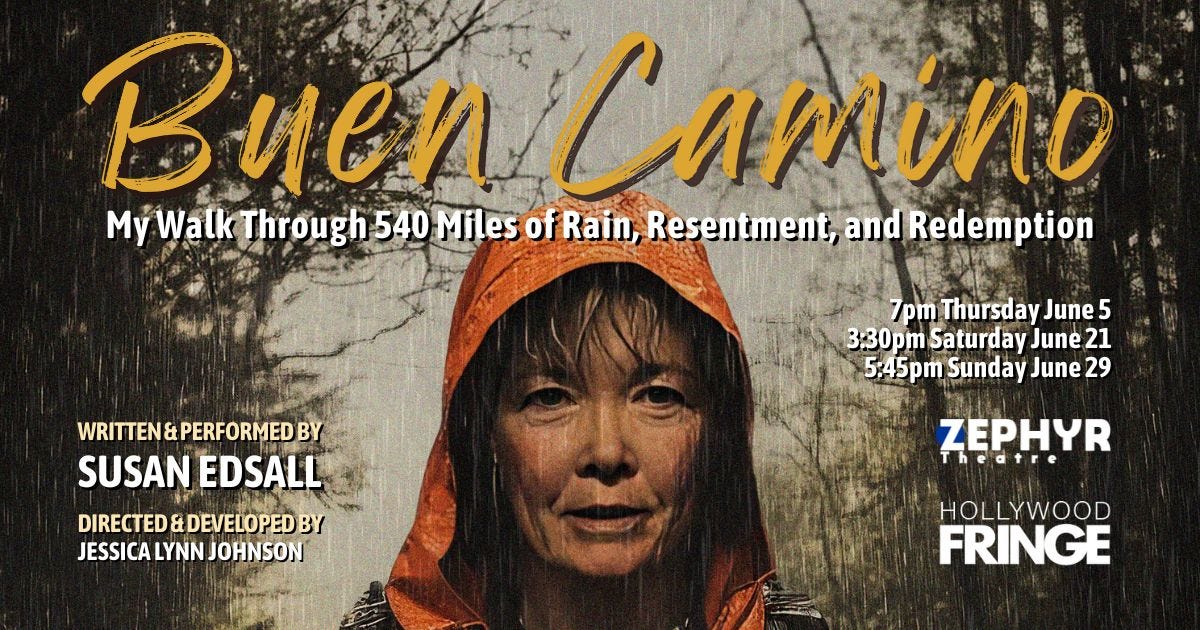

West Coast friends (and friends of friends)… I’m performing Buen Camino at the Hollywood Fringe Festival and would love to see you there.

7pm Thursday June 5 | 3:30pm Saturday June 21 | 5:45pm Sunday June 29

The Gist of It All

My mom has dementia, and Dad has committed their life savings to around-the-clock care so she can die where she lives. The trouble is, she isn't dying. Several years ago, during what we were all certain was her last Christmas, my sister assured her that if she was ready to go, she should go, that we would manage. But my mother wasn't ready.

On my most recent visit, Mom lies on the couch in the living room. It’s hot and smells like lotion and the sweat of sleep. She says she wants to go home. Which would be fine except she is home.

This is where she has spent virtually every afternoon of her life devouring romance novels—Nora Roberts, Nicholas Sparks, Sidney Sheldon—wrapped up in a world of action and desire and women who, somehow, prevailed.

I sit close to her, noticing her serviceable, rubber-soled shoes. Mom has traded in so much to grow so old. She used to own dozens of what she called “shack-up shoes”—heels in patent leather, brocade, two-toned suede, jewel-embossed canvas. Always heels. She used to wear tailored pants with an invisible zipper up the side. She used to drive.

I take her hand. Arthritis angles the tips of her fingers sideways, leaving only her thumb and index finger, which she uses like a claw. The caregivers have fitted a small cushion of fleece into her palm so her nails won’t puncture her skin. Her skin is velvet, milky white, it has the feel and smell of powder.

“Three weeks ago I had twin boys.” She holds my gaze with her watery blue eyes. “They died.”

Dad has sternly instructed me not to talk to Mom about babies because she gets obsessed with them, unable to sleep.

“Are you sure, Mom?”

“Certainly I'm sure.” She brings a shaky finger to her eye. “It was heartbreaking.”

I glance up. Dad has settled himself in front of the news while Seyem, tonight's caregiver, starts dinner.

“Tell me about the babies, Mom.”

She picks at the edge of the crocheted afghan. “I wanted those children.” She closes her eyes and shakes her head.

“I'm sorry, Mom.”

“Me, too.” She opens her eyes and seems satisfied to move to another subject. “You know, I think I'm at the end of this part of my journey. Now I'm gathering things up and getting organized.”

I laugh. My mother was always organized, forever cleaning closets, weeding out her recipe box, taking clothes to Goodwill.

She clasps her hands together on her lap, every fragile bone and knotted joint pressing against her skin. “Mostly I'm trying to figure out what the gist of it all was.”

“The gist?”

When she stretches her legs, her striped socks poke out the bottom of the afghan. “You were always so good at understanding the meaning of things.” Something catches her eye and she points at the rod holding the nubby drapes hanging from brass rings in our living room. “Look! There they are. The next chapter is all new people. I don't know their names yet.”

I look at the curtain rod. “Why don't you ask them?”

“Oh, I think I'll wait. They'll tell me when they're ready.”

Mom is shy. It's hard for her to make new friends. Fifteen years ago, Anita, a woman in her church, befriended Mom, picking her up to go out for lunch. Mom loved those afternoons. They hadn't been friends for more than six weeks before Anita got diagnosed with cancer and was dead within a month. Mom never made another new friend. She called once asking if I would make sure Pat Newby, the soloist at her church, sang “His Eye Is on the Sparrow” at her funeral.

I scoop butter mints out of the bowl on the tray and hand one to Mom.

She reaches for it, the diamond my father gave her for their 25th anniversary sagging on her small finger. “Do you feel better about yourself?” she asks.

My heart bangs into my throat. We have never talked about anyone feeling better about themselves. We talked about how to get wine stains out of cotton shirts, how early you can plant flowers without risking frost. “Yes, Mom. I do. I've been working hard on that.”

She sucks on the mint and smiles. “Mmm. Good.”

Reaching across, I straighten a straggly hair on her forehead, trying to make it curl. She always cared about her hair, fussing with a hand mirror to see the back of her head, where she tried to fix what she called “the holes in her head,” hair that curled in opposite directions, leaving a flat spot. She sleeps nearly twenty hours a day now, turning her curls to fuzz. “Do you feel better about yourself, Mom?”

“Well, I sure hope so. It's hard, though, isn't it? I got down and I couldn't get back up.”

The smell of fried onions signals dinner. Soon Seyem will hustle her up to the table where she’ll feed Mom with a child's spoon. Mom won't want to eat, but Dad will insist. When the aches in her body drive her to say, “Oh, oh,” Seyem will joke about a family named the Ohs who have arrived after being out for the day. I will have to leave the room so I don't scream: She just wants to go to bed. Can't she now, finally, have what she wants? Dad will want her to stay awake at least until eight. Tomorrow morning, the caregivers will know that Dad likes her up and dressed for breakfast.

“What do you mean, Mom, that it's hard?”

She tries to find the words. “Well, I just got down, you know how it is, and I didn't have the power to get up.” I want to run my thumbs along the three crooked seams that cut across her forehead, frown marks that won't polish away. “I read an article about it, it’s true for lots of women. They get down and they just can't get back up.” She settles her hands on her chest. “I'm in good company, I guess.” The resignation in her voice makes it sound like small consolation.

“I wonder if they really can get up, Mom, but they just think they can't.”

Mom looks me in the eye. “I disagree with you.”

I lean in. I love her clear, unapologetic dissent. Mom rarely dared to disagree—the cost was too high. She bucked Dad once and voted for Bill Clinton. The economy got stronger, international relations improved. Mom took on a small smug expression during the evening news. Then came Monica Lewinsky, the Starr Report, the cigar, Dad's I-told-you-so. “What do you disagree with?”

“Well, I couldn't lift myself up. It takes so much strength.” She smooths the afghan. “And it was frightening.”

I want to listen to her talk all night. I want every single feeling she has ever swallowed whole, every thought she has ever silenced to cannonball out of her, destroying my illusions about her grace and her satisfaction and her equanimity. I want her to scream bloody murder.

Seyem calls in. “Okay Marcia! Time for dinner!”

Mom rolls her eyes. “I guess I have to be the hostess now.” She peers at me. “I don't want to go because I'm afraid you won't be here when I get back.”

“I'll be here, Mom. I think I'll join you for dinner.”

“That would be great.” She pats my knee. “My darling daughter.”

“My lovely mother.”

“Aren't we lucky?”

As I watch Seyem bundle her into her wheelchair, I wonder if, as difficult as Mom's life seems to me right now, I have underestimated its difficulty all along. Maybe what's disturbing to us isn't Mom's dementia, but that she's finally speaking her mind. Perhaps dementia hasn't made her life worse, but, in a way important to her, has made it better, loosening the censor that kept her silent all those years. Maybe Mom hangs on because she feels liberated, and that feels good.

Maybe that's the gist of it all.